The Circle of Life: Manager Research and Lifecycle Analysis

The lifecycle concept may be familiar ― it’s applicable to business strategy, product management, life and the rise and fall of nations. It is our belief that it also applies to manager research and due diligence.

Lifecycle stages could be described in asset-management terms by these characteristics:

An emerging manager oversees limited capital ― typically seed investments, or sourced from friends and family. Offerings are likely limited to a core strategy, although the investment process should be expected to be well-defined, and personnel will be limited to a key person or concentrated investment team. Infrastructure should be sufficient, but under development, and there may be substantial reliance on third parties.

In the growth stage, a manager begins to see success in the performance or marketing of core strategies and may begin adding complementary strategies. Non-investment aspects like operations and sales will benefit from development.

A mature manager may be realizing success not only in the performance or marketing of a flagship strategy, but across multiple strategies. Operations should be fully built out, and assets under management are at or approaching capacity. Succession planning should be a key consideration.

A manager in decline has grown assets under management (AUM) beyond capacity and may likely be losing assets. Lack of planning to accommodate a generational transfer of talent may result in team departures or, eventually, ownership changes.

In theory, a lifecycle could extend for years or decades, so it’s not intended to prescribe a particular timeline. But we see validity ― and a valuable business impact ― in considering our manager relationships in this context.

What Does This Mean for SEI?

- From a marketing standpoint, we want to know how many managers we have in each lifecycle stage in order to improve our competitive position in the marketplace.

- From a business and financial point-of-view, there are practical implications. We pay significant fees to managers, and we can see clearly that a manager’s aptitude and willingness to price their business will change over the lifecycle of a strategy.

- From a platform perspective, we don’t want to have too many managers in the mature or declining stage given the impediments to performance it suggests.

A Framework for Lifecycle Analysis

There are two dimensions in which lifecycle analysis applies: to the investment management firm itself and to the strategy.

We believe these two dimensions need to be disengaged because, for example, mature firms are capable of developing emerging strategies, and this dynamic could present an attractive opportunity in the right setting. As another example, we would expect an emerging strategy at an emerging firm to embody a distinct and compelling set of attributes.

Exhibit 2 provides a simplified template of the components associated with analyzing a manager’s strategy and firm evolution in a lifecycle context.

As Exhibit 2 shows, we have endeavored to consider the components of a manager’s strategy and firm in terms of whether they represent benefits or drawbacks. For example, we have found it’s typically much better if a strategy has fewer assets under management (AUM) than more. Usually the strategy has capacity and room for growth, and managers are eager to generate performance.

If AUM can be measured empirically, attitude to capacity requires a judgement call. Some managers are rapacious in their appetite for new assets, which is not necessarily beneficial to us. Here, the metrics we apply are based on our observations of the relationships we establish with managers.

We have operationalized this approach to reflect both quantitative and qualitative measures. A key advantage to scoring in this way is that we can avoid hard thresholds for consideration, like a minimum or maximum AUM, in favor of a more comprehensive manager view given the real-world possibility that a strategy might be worth strong consideration on a number of other measures.

How Do Our Managers Stack Up?

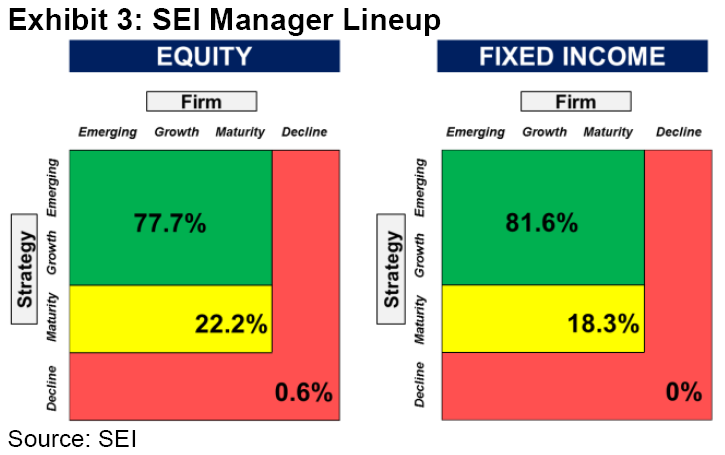

We analyzed our active manager lineup ― composed of roughly two-thirds equity strategies and one-third fixed income ― to establish a distribution along the lifecycle curve. We used a grid to account for the two dimensions: strategy and firm.

Exhibit 3 shows the percentage of managers that we believe fit into each stage today. The color-coding is intended to show where lifecycle characteristics come together to work in the investor’s favor, and obviously those on the right and bottom perimeters should be avoided. Generally, movement down or to the right implies diminishing future prospects.

These findings should be reassuring in aggregate: 78% of our equity strategies and 82% of our fixed income strategies reside in the emerging and growth stages. The implications become more evident as we break this information down into strategy and firm distributions.

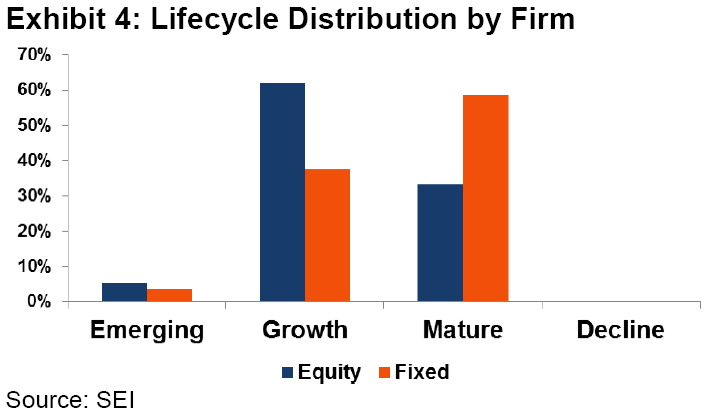

Let’s look at this first in terms of the firm. Exhibit 4 depicts an interesting dichotomy between equity and fixed income regarding the number of firms that we believe are in the growth stage versus those in the maturity stage.

This contrast is at least partially attributable to market structure. Many of the fixed-income firms we work with are well-established with significant scale. Opening a new fixed-income management firm is considerably more difficult than an equity firm, where a trader can quickly and easily go independent, register with an electronic brokerage platform and be open for business.

Mature fixed-income firms need not necessarily be viewed negatively because economies of scale and market access represent important advantages in the fixed-income market.

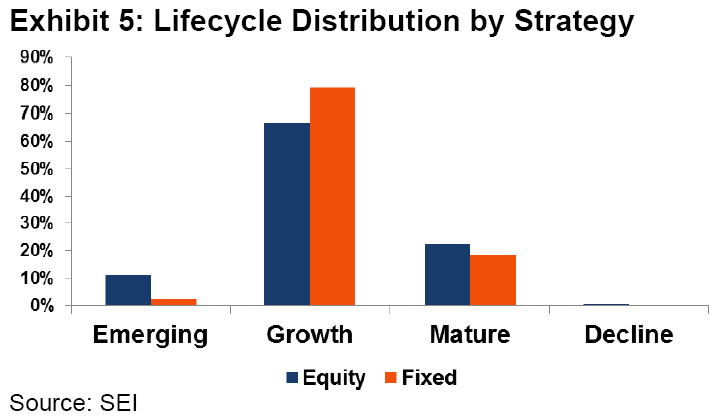

From a strategy point of view, Exhibit 5 shows that there are fewer differences between equity and fixed income with respect to the proportion of managers in each lifecycle stage.

Here lies an important point of focus: how many managers do we believe have strategies currently in the mature stage? We have to question how much potential for alpha generation remains in a mature strategy given the behavioral tendencies that can arise alongside significant AUM levels and declining capacity. An excessively conservative management mentality can take hold as a result of the desire to retain assets, whereas the manager of an earlier-stage strategy seeks to develop an impressive track record in pursuit of new assets.

In Practice: Small-Cap Equity

Perhaps the more appropriate concern is to consider what we should be doing with managers that have strategies in the mature stage.

Let’s explore a real-life example centered on our current universe of U.S. small-cap strategies.

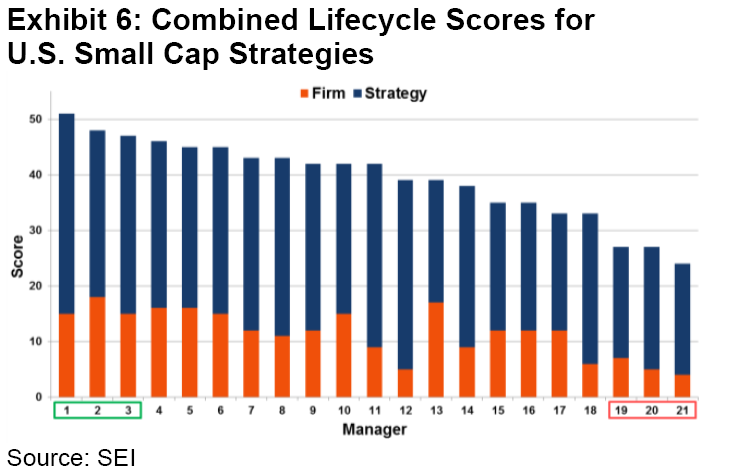

We currently have 21 strategies that sport “Recommended or “Approved” ratings, as can be seen listed in Exhibit 6.

We develop separate scores for the strategy and the firm: the higher a manager’s score, the closer they are to the emerging stage, and the lower their score, the closer they are to decline. Exhibit 6 depicts each U.S. small-cap manager’s combined strategy and firm score.

We boxed three managers with the highest combined scores in green, representing the emerging end of the scale. At the low end, we boxed three strategies in red that are the most mature managers on our current roster.

Ideally, from a business point of view, we should recognize the maturation of our managers along the lifecycle curve and plan to recycle money out of the most mature strategies into emerging opportunities.

That is exactly what we have been doing. We hired these three emerging U.S. small-cap managers in the last year or so, and their mature counterparts are in the process of seeing their assets reduced or sunsetted.

Applying our framework for lifecycle analysis to manager research provides us with a different lens through which we can view the candidacy and conduct ongoing monitoring of managers. This is an active engagement that we believe will add value in a separate dimension from our ongoing work analyzing people, philosophies and processes.

Glossary

Alpha: Alpha refers to returns in excess of the benchmark.

Qualitative: Qualitative refers to security analysis based on analyst research and subjective views.

Quantitative: Quantitative analysis is based on computer-driven models.

Important Information

Managers discussed involve analysis across SEI’s entire platform. Managers may not be available in your jurisdiction. Manager research updated as at 4 May 2016.

Important Information:

Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.

Investments in SEI Funds are generally medium to long term investments. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may not get back the original amount invested. Additionally, this investment may not be suitable for everyone. If you should have any doubt whether it is suitable for you, you should obtain expert advice.

No offer of any security is made hereby. Recipients of this information who intend to apply for shares in any SEI Fund are reminded that any such application may be made solely on the basis of the information contained in the Prospectus. This material represents an assessment of the market environment at a specific point in time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events, or a guarantee of future results. This information should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding the funds or any stock in particular, nor should it be construed as a recommendation to purchase or sell a security, including futures contracts.

In addition to the normal risks associated with equity investing, international investments may involve risk of capital loss from unfavourable fluctuation in currency values, from differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic or political instability in other nations. Bonds and bond funds are subject to interest rate risk and will decline in value as interest rates rise. High yield bonds involve greater risks of default or downgrade and are more volatile than investment grade securities, due to the speculative nature of their investments. Narrowly focused investments and smaller companies typically exhibit higher volatility. SEI Funds may use derivative instruments such as futures, forwards, options, swaps, contracts for differences, credit derivatives, caps, floors and currency forward contracts. These instruments may be used for hedging purposes and/or investment purposes.

While considerable care has been taken to ensure the information contained within this document is accurate and up-to-date, no warranty is given as to the accuracy or completeness of any information and no liability is accepted for any errors or omissions in such information or any action taken on the basis of this information.

This information is issued by SEI Investments (Europe) Limited, 1st Floor, Alphabeta, 14-18 Finsbury Square, London EC2A 1BR which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Please refer to our latest Full Prospectus (which includes information in relation to the use of derivatives and the risks associated with the use of derivative instruments), Key Investor Information Documents and latest Annual or Semi-Annual Reports for more information on our funds. This information can be obtained by contacting your Financial Advisor or using the contact details shown above.